Leonard had an eye for what was wrong. His negativity bias was stronger than even he would have liked. He’d spot anything that was “off” in the present and anticipate anything that could possibly go wrong in the future. This wasn’t just occasional catastrophic thinking, but a habit of perception that colored everything he saw.

When he walked into the apartment he’d notice immediately that his girlfriend hadn’t washed her coffee cup, and miss completely the flowers she’d bought for him. He ruminated on the many possible disasters that could ruin their upcoming trip, and not a bit about what could go right. His conversation was dominated by what other people were doing wrong, and what he might get wrong if he wasn’t overly-conscientious.

Worse, he couldn’t be happy until it was all fixed. And since that was impossible, he eventually got depressed.

This is the 2nd in a short series of posts about compulsive personality and depression, more specifically why people who are compulsive are particularly susceptible to depression. (You can find Part 1 here.) The perfectionism and conscientiousness so characteristic of the compulsive personality can lead to a satisfying life if managed well. But far too often they lead us to focus on what’s wrong. And that makes us very unhappy–if not completely depressed.

Before I jump in, I need to say that if you are depressed, please seek help from a licensed mental health professional. This blog cannot substitute for the specific care that a therapist can offer.

Contents

The Roots of Negative Perception

If we get lost in depression and want to find our way out, it helps to understand how we got here, our past. By our past I don’t just mean abandonments, neglect, trauma, loss, or whether my sister tortured me when I was a kid. (She didn’t, by the way).

I mean that we also need to take into consideration the hundreds of thousands of years of evolution before that that brought us to where we are today. This past has shaped the genes that determine our personality at least as much as what we encounter after birth.

You come with a long history, like it or not. As Carl Jung said, you have a two million year old human being inside of you. And, I would add, he’s a really grumpy old guy.

It’s easy to be mislead by a simplistic emphasis on what’s happened to us in the 20 to 60 years we’ve been alive. While our environment, that is, our family and our culture, certainly shapes the genes we’re born with, focusing exclusively on environment may leave us feeling as though we are victims of our circumstances, rather than empowering us to discover and develop who we are naturally, and what we can do to make ourselves happier. More on that in a moment.

Part I: Low Mood Can Compensate for Unrealistic Expectations

In my last post I wrote about how low mood has been adaptive from an evolutionary perspective. By reducing our energy when we run into a wall, low mood has helped us to let go of rigid positions and walk away from unrealistic expectations. Understood this way, we may be able to see a purpose in low mood rather than go full hog into depression.

Since compulsive people tend to set expectations too high, they often experience compensatory low mood when they themselves, or the world, don’t meet those expectations. But because we think of ourselves as enlightened, reasonable and “modern,” it never occurs to us that our psyche might be trying to tell us something.

Scanning for Trouble

In this post I’ll focus on another way that evolution has shaped us: the compulsive tendency to focus on what’s wrong, and to focus on that so much that it prevents better moods.

Nature has programmed us to scan for things such as:

- physical dangers

- social status (our own, those close to us, and those we feel competitive with)

- reliability

- depleted resources

We were more likely to survive and pass on our genes if we focused on these potentially dangerous situations. But for some of us, this focus has remained dominant, even though it doesn’t make us happy–and may not even increase our chances of surviving. You might think of these as leftovers, best thrown out before they stink up the fridge. But that’s not quite accurate, and I think a better metaphor is that of a wise, but rather old, mentor, whose advice needs to be filtered for contemporary relevance. They’re not always wrong.

How Evolution Shows Up In Your Home

Here’s what concentrating on what’s wrong can look like. You focus on:

• The kitchen not being spotless because it could mean that there are dangerous germs lurking in there somewhere.

• Your husband has questionable social skills so your status is low.

• Your wife seems to care more about her friends than you so she’s not reliable.

• Your checking account has less than you’d like so you’re in danger of depleting your resources.

Beneath all this is an “instinct” to make things “safer” so that we’re more likely to survive. Taken too far, we lose the original point for ever having a kitchen, a partner or a bank account. They don’t have to be perfect to be in our best interest.

The Compulsive Negativity Bias

There is no single gene that causes this attention to what’s wrong. It more like a module in the brain, a network of neurons caused by an assortment of genes, which predisposes us to focus on what seem like imminent “dangers.”

To simplify greatly, this module causes the negativity bias, which is “the propensity to attend to, learn from, and use negative information far more than positive information.” We’ve developed so that avoiding bad situations motivates us more than taking advantage of good ones.

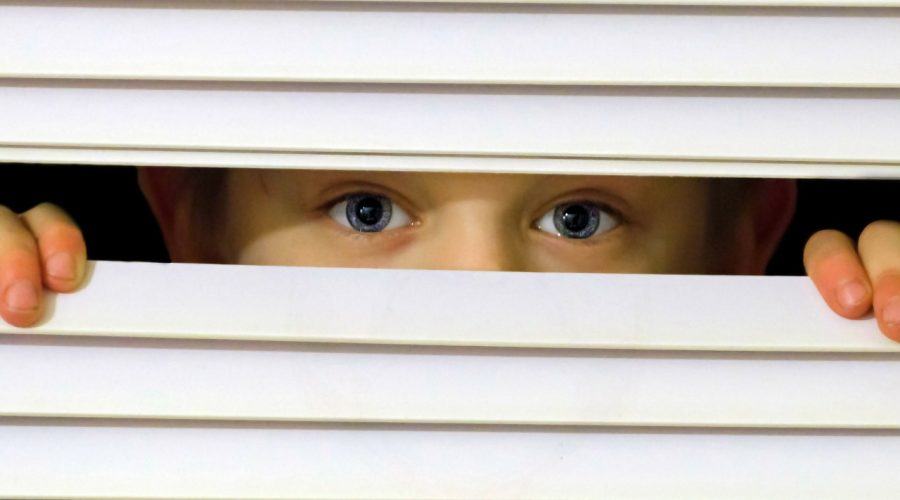

You won’t survive a fire if you don’t run away from it, but you will survive if you don’t notice that single blueberry in the bush. Notice how you feel in reaction to each of these photos:

Does one grab your attention more than the other?

It doesn’t matter if this negativity bias module makes us happy or not. It makes our genes more likely to get passed on if we’re always focused on what needs fixing.

But, you might say, lots of people could care less when things aren’t right. For sure. They were absent the day those genes were handed out. Not everyone is like this.

And other people seem to have gotten more than their fair share of these genes.

We call these people obsessive-compulsive.

One study found that people with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder had more accurate visual acuity than those that didn’t. They see details that others never notice. But this blessing can become a curse if you can’t close your eyes or focus on something other than problems.

Of course if your early environment was unstable, it would have exaggerated these tendencies to look for what could go wrong. Pre-empting problems was a reasonable strategy if your family offered no security and you had to fend for yourself.

Nature’s Deceptions: Scan, Fix, Repeat, Get Depressed

You’d think that nature would give us a payoff for noting what’s wrong and fixing it, but it’s stingy. You get a brief pay-off, but it won’t last long.

These modules often fool us. They cause a delusion that leads us to do things that will improve our chances for survival, imagining we’ll feel good. But we often end up feeling very dissatisfied soon afterward.

We start out thinking, “This is gonna be great!” But the pay-offs for the seeing problems and remedying them don’t last long, and you’re scanning for the next thing to fix to get another little hit of endorphins.

Scan, fix, repeat. If you’re lucky. More likely you’ll scan, feel frustrated, repeat.

It’s part of the life strategy of compulsives to try to take control and fix things in an effort to avoid uncomfortable emotional states.

But this gets depressing after a while.

We’re lured into trying to fix, but soon after, we experience dissatisfaction. If we were completely satisfied by fixing problems we’d just sit on our tush and live happily ever after once we indulge this tendency. But then we wouldn’t pass on our genes.

This is especially depressing for compulsives because we’re under a second delusion: we imagine we can and should control it all, as if it’s our responsibility to. And of course we can’t and it isn’t.

All of this applies to how we see ourselves as well. We focus on our less attractive aspects, which might seem like it would help our performance, but in the long run does not. And it magnifies the depression.

Additional Short-term Payoffs for Negative Thinking

Evolutionary and environmental causes are bad enough. But their are still additional possible sources for a stubborn case of negativity bias, including our own insecurity about ourselves.

If I get some gratification out of proving to myself that the world is morally decrepit, hopelessly stupid, and remarkably ugly, I might feel motivated to pile it on. If my negative insight proves to me that I at least know better, and so I’m no worse than everyone else, I will revel in cynicism. We reach for reassurance of superiority. We reap depression.

Can I do anything about it?

Here are the three factors that determine how happy or depressed we are:

- Genes–nature

- Environment, family circumstances, social setting–nurture

- Intention

Our conscious intentions, our choices about how we think and what we do, also determine which end of the happiness spectrum we live on.

Research psychologist Sonia Lyubomirsky has concluded from her research that while we have a set-point of happiness determined by our genes, this accounts for only about 50% of our mood. Circumstances determine only 10%.

Intentional activity, what we do and how we think, accounts for the remaining 40% of our happiness.

How to Achieve Change

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt uses a metaphor to help us understand how we change. He suggests we think of ourselves as composed of an elephant and a rider. The elephant is this older, genetically determined and socially programmed part of us. The rider is the part that with intention, persistence and determination can slowly train the elephant to go in a different direction.

While therapy is the first line of defense, there’s no reason you can’t, in addition, design your own program, complete with lists and goals, focusing the determination that comes with the compulsive personality, to retrain your perspective so that your elephant isn’t always lumbering off to the land of depression with you helplessly on top.

“The Practice of And”

Since we’re up against hundreds of thousands of years of programming, we need to make conscious efforts to counteract the negativity bias.

I’ve taken up a tool that I call “The Practice of And.” I try, every time a negative thought or feeling comes up, to acknowledge it, and note that there are also good things. I visualize two canisters, one held in each hand–one containing the bad, the second containing the specific good that I choose to focus on.

Yes, the car needs an expensive repair, and the weather is beautiful.

Yes, a client is going through some disturbing issues, and I can breathe deeply.

Yes, someone put up a negative review of one of my books on Amazon, and all the other reviews are good.

I have found this helpful. But don’t take my word for it. Consider these words of wisdom from someone who has experienced profound suffering and still refuses to be dominated by it. Vietnamese Zen meditation teacher, Thich Nhat Hahn witnessed the killing of hundreds of his countrymen in the Vietnamese war, yet he encourages us to see the beauty in the simple acts of life:

“Life is filled with suffering, but it is also filled with many wonders, such as the blue sky, the sunshine, and the eyes of a baby. To suffer is not enough. We must also be in touch with the wonders of life. They are within us and all around us, everywhere, anytime.”

Leonard Trains His Elephant

Here’s how Leonard became less focused on what’s wrong:

• He identified as often as he could when he was scanning for what was wrong.

· Name and tame. He called it his hyper-vision.

• He tried not to judge himself for his negativity bias.

· It was a part of him that just needed to be reigned in.

· He let himself feel the emotions–fear and anger–which he tried to avoid by judging and fixing.

• He tried to remember the original purpose of his hyper-vision and use it only where appropriate.

· It was very helpful for work itself, but terrible when applied to his co-workers.

• He also explored it’s secondary purpose, the fringe benefits of thinking he knew better than everyone else.

⋅ It was a bittersweet victory that he decided he no longer needed and could no longer afford.

• He practiced the most important skill that a compulsive can develop: letting go.

· It felt extremely strange, but he had to let go of his sense of ethical duty to make sure that everything was done properly.

• He put two more meaningful goals in its place:

· An intention to value peace of mind over fixing everything, and

· An intention to value everything he already had.

Come visit again when we continue with Part 3: Stepping Off The Compulsive Hedonic Treadmill.

Press the subscribe button below and you’ll get the next installment delivered to your inbox.

Discover more from The Healthy Compulsive Project: Help for OCPD, Workaholics, Obsessives, & Type A Personality

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.